Too intelligent, too beautiful, too strong, too much of a commie? Chantal Montellier has often been viewed a mix of fear and fascination – a fact that has caused her art to be relegated to second place in the history of her critical reception, when it should have garnered full attention. This exhibition aims at focusing on a highly prolific period in Montellier’s career, to firmly inscribe it within the history of comics as one of the most politically relevant of its time.

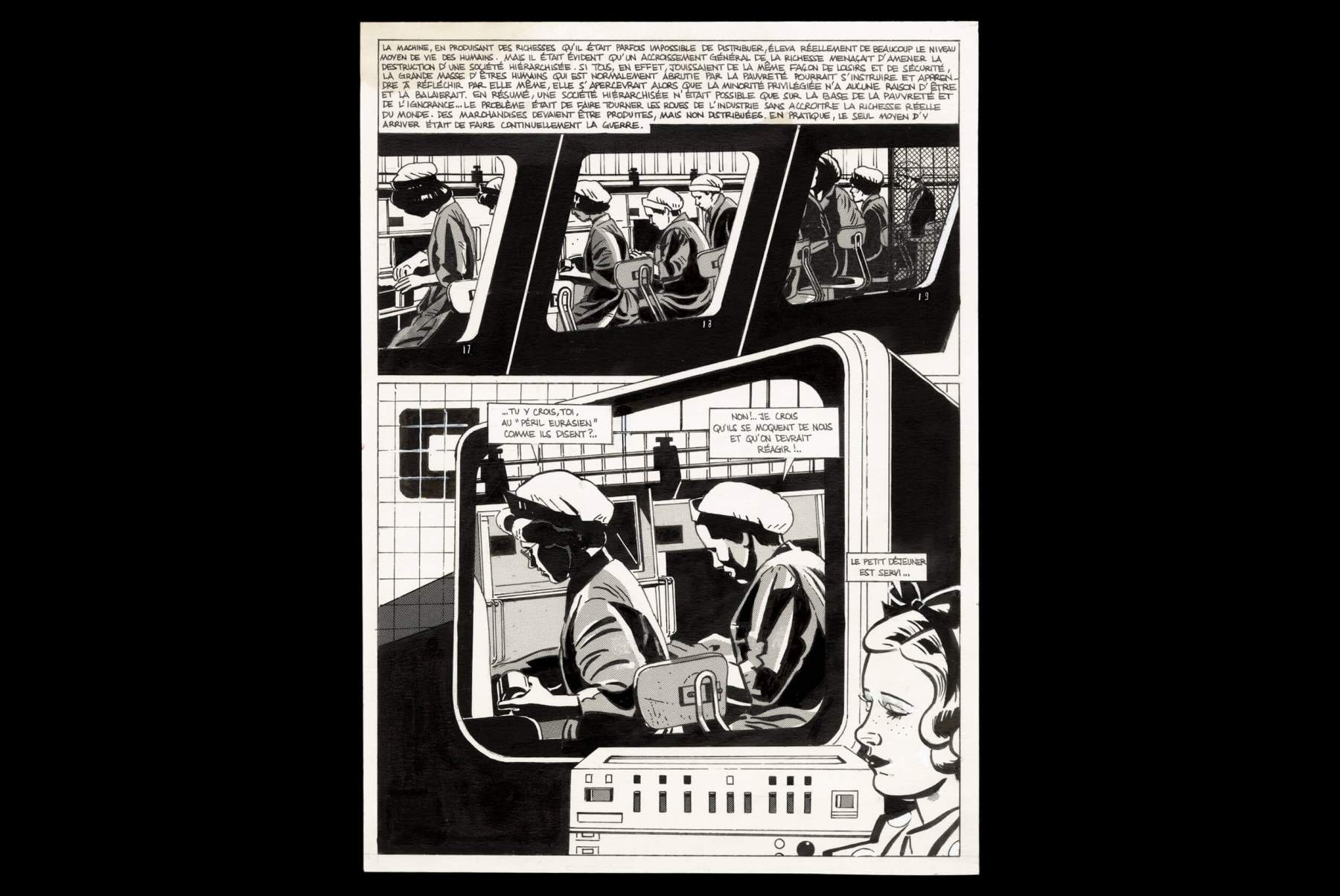

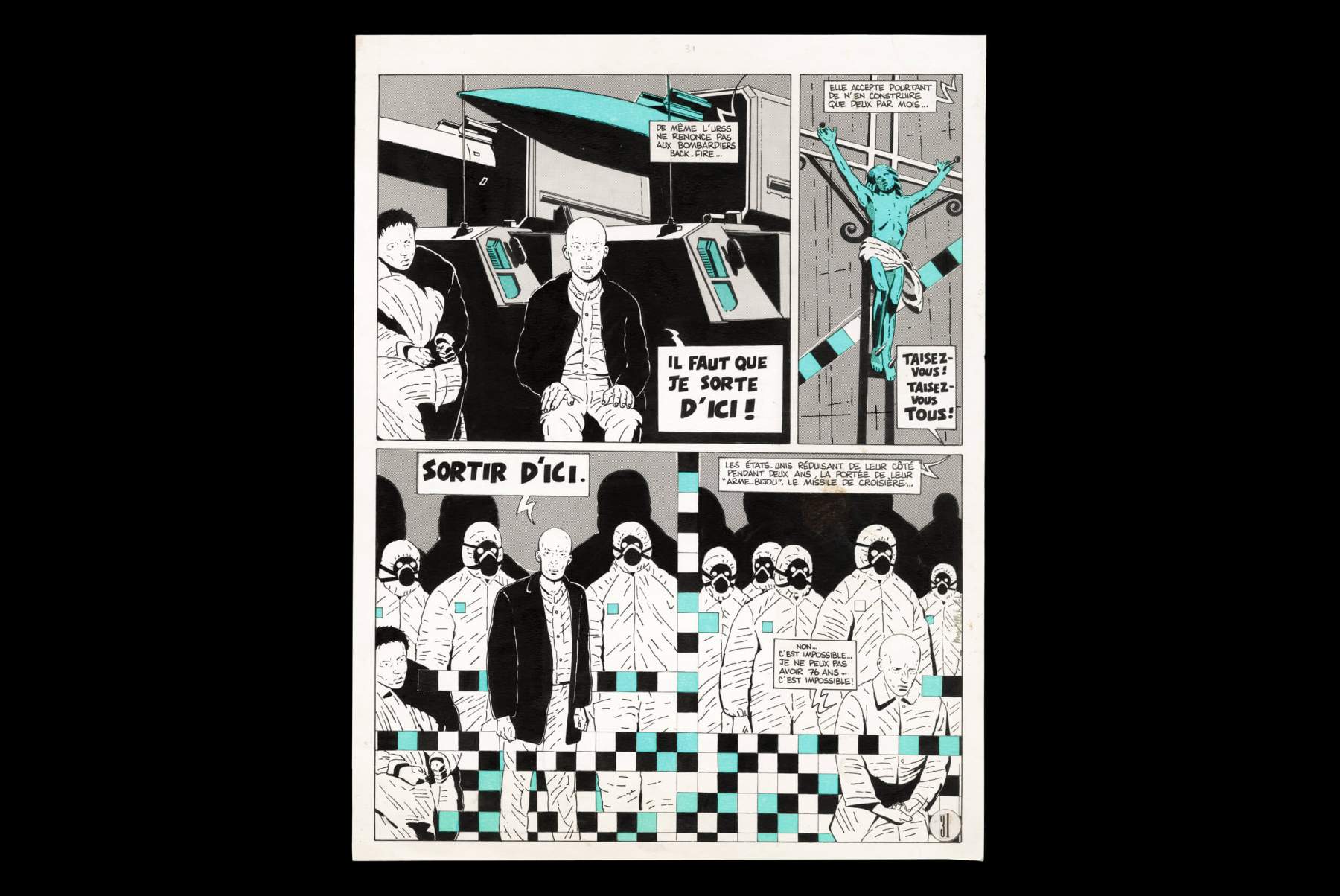

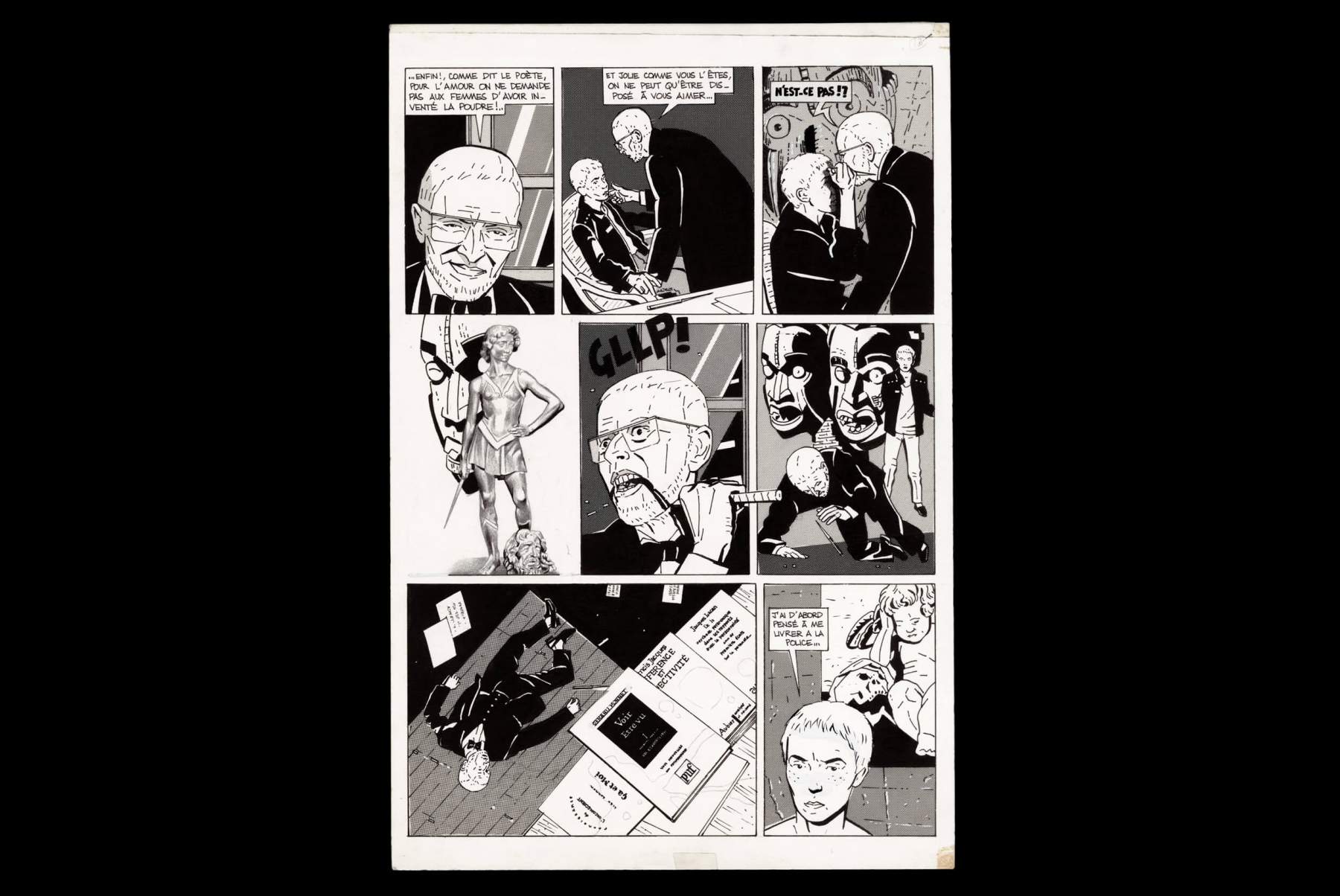

Between 1978 and 1994 – from her first pages in Charlie Mensuel, Ah ! Nana and Métal hurlant to the publication of the third (and sadly, last) installment of Julie Bristol’s adventures by Éditions Dargaud, Montellier created a most unique body of work in the history of francophone comics. Its consistently critical relation to the world singles out Montellier’s work within the landscape of independent comics.

When Montellier started publishing, it may have been unthinkable to some that a work so unashamedly and effortlessly political had created by a woman. Those who had a hard time grasping the full extent of her artistic presence then and those keeping a conspiracy of silence around her work now might very well be the same. And so, throughout Montellier’s entire career, the reception of her work has unfortunately been textbook material for feminist art history.

This exhibition aims at making visible once more a work made invisible through many editorial failures. It also means to contribute to the conservation of Montellier’s work, from a resolutely matrimonial perspective.

While Montellier was published by the greatest publishers in the history of francophone comics in the 1980s – Les Humanoïdes associés, Futuropolis, Casterman – none of her historical publishers has republished any of her works for now. Neither 1996, nor Shelter, nor Wonder City (the three episodes of her social fiction trilogy) have been republished by Les Humanoïdes associés. Julie Bristol’s three adventures have never been issued as a single volume, and republications of masterpieces such as Les rêves du fou, Rupture or Le sang de la commune are long overdue.

Retrospectively, Montellier’s consistent approach to political critique as artistic matrix may appear as one of the rare counterbalances to opportunistic shifts in comics publishing that occurred throughout the history of independent comics, which bore witness to the replacement of the blend of eroticism and science fiction characterizing Métal hurlant by the discreet charms of the petite bourgeoisie in the pages of À suivre.

At a time when the medium began to emerge beyond the children’s sections in kiosks and bookstores, Montellier’s production stood out as authentically grown-up among the mass of European comics released in the 1970s.

In Montellier’s work, the critique of the economy of politics is enriched by a critique of control society, a critique of consumer society, a critique of patriarchy, and a critique of state violence.

Against regressive escapism or deleterious forms of nostalgia, Montellier’s work summons the chill of reality. Both realistic and dystopian, her stories abound in images that only the moderate will find extreme.

In Montellier’s world, Paris is haunted by murdered Communards; shopping malls are operated as the laboratories of indoor social experimenting; men are – literally – crocodiles; eugenism is computer-assisted; corpses are used to sell second-hand cars; and Big Brother looks like a bald old man whose face we read as sweet because of our cultural conditioning. And if Montellier depicts the psychiatric institution with documentary-like attention to detail, she also presents it as the other side of a world in which the most dangerous lunatics are actually the ones in command and in possession of the nuclear codes, always on the right side of power. As for Montellier’s handsome state-sanctioned assassins (a.k.a. police inspectors), their handling of police blunders is pure bureaucratic routine.

Montellier’s use of metaphor does not only express a deeper reality: more often than not, it also transcribes actual truths. That is because dystopia is never far from the reality it represents allegorically, or even actually re-presents. Sometimes a simple re-description – in Les damnés de Nanterre, the depiction of France in the days when Charles Pasqua was minister of the interior – is enough to bring out the dystopian colors of the real.

Montellier took the path less traveled, stubbornly determined to think for herself and through images, with the deep-rooted belief that comics can do better than merely entertain (even if experimentally), and that good comics may take the path less traveled – the path of politics? Is it the singularity of her vision that caused a fright?

The choice of the exhibition as format to see, read, and reflect upon Montellier’s work once more, within the context of a contemporary art venue, makes sense to us because Montellier’s comics command a high degree of attention to form as the outcome of her critical thinking. Faithful to the “48CC” format, Chantal Montellier is no graphic novelist (although she is also a novelist, period), but an artist working with and through the comic strip template. A large part of her work may be overlooked if one is not cautious to her intricate constructions, her multiple use of echo, symmetry, mise-en-abyme – in short, if one is not interested in the reflexive side of a work that appeals to its reader/viewer’s intelligence, rather than their consumer instincts. R.B., V.G., É.M. and F.W.